The Chinese have called it their “Underground Great Wall” — a vast network of tunnels designed to hide their country’s increasingly sophisticated missile and nuclear arsenal.

For the past three years, a small band of obsessively dedicated students at Georgetown University has called it something else: homework.

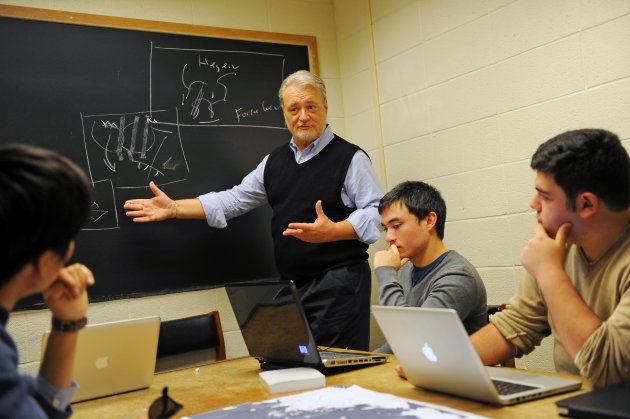

Led by their hard-charging professor, a former top Pentagon official, they have translated hundreds of documents, combed through satellite imagery, obtained restricted Chinese military documents and waded through hundreds of gigabytes of online data.

The result of their effort? The largest body of public knowledge about thousands of miles of tunnels dug by the Second Artillery Corps, a secretive branch of the Chinese military in charge of protecting and deploying its ballistic missiles and nuclear warheads.

The study is yet to be released, but already it has sparked a congressional hearing and been circulated among top officials in the Pentagon, including the Air Force vice chief of staff.

Most of the attention has focused on the 363-page study’s provocative conclusion — that China’s nuclear arsenal could be many times larger than the well-established estimates of arms-control experts.

(Graphic: Evidence of China’s nuclear storage system)

“It’s not quite a bombshell, but those thoughts and estimates are being checked against what people think they know based on classified information,” said a Defense Department strategist who would discuss the study only on the condition of anonymity.

The study’s critics, however, have questioned the unorthodox Internet-based research of the students, who drew from sources as disparate as Google Earth, blogs, military journals and, perhaps most startlingly, a fictionalized TV docudrama about Chinese artillery soldiers — the rough equivalent of watching Fox’s TV show “24” for insights into U.S. counterterrorism efforts.

But the strongest condemnation has come from nonproliferation experts who worry that the study could fuel arguments for maintaining nuclear weapons in an era when efforts are being made to reduce the world’s post-Cold War stockpiles.

Beyond its impact in the policy world, the project has made a profound mark on the students — including some who have since graduated and taken research jobs with the Defense Department and Congress.

“I don’t even want to know how many hours I spent on it,” said Nick Yarosh, 22, an international politics senior at Georgetown. “But you ask people what they did in college, most just say I took this class, I was in this club. I can say I spent it reading Chinese nuclear strategy and Second Artillery manuals. For a nerd like me, that really means something.”

For students, an obsession

The students’ professor, Phillip A. Karber, 65, had spent the Cold War as a top strategist reporting directly to the secretary of defense and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. But it was his early work in defense that cemented his reputation, when he led an elite research team created by Henry Kissinger, who was then the national security adviser, to probe the weaknesses of Soviet forces.

Karber prided himself on recruiting the best intelligence analysts in the government. “You didn’t just want the highest-ranking or brightest guys, you wanted the ones who were hungry,” he said.

In 2008, Karber was volunteering on a committee for the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, a Pentagon agency charged with countering weapons of mass destruction.

After a devastating earthquake struck Sichuan province, the chairman of Karber’s committee noticed Chinese news accounts reporting that thousands of radiation technicians were rushing to the region. Then came pictures of strangely collapsed hills and speculation that the caved-in tunnels in the area had held nuclear weapons.

Find out what’s going on, the chairman asked Karber, who began looking for analysts again — this time among his students at Georgetown.

The first inductees came from his arms-control classes. Each semester, he set aside a day to show them tantalizing videos and documents he had begun gathering on the tunnels. Then he concluded with a simple question: What do you think it means?

“The fact that there were no answers to that really got to me,” said former student Dustin Walker, 22. “It started out like any other class, tests on this day or that, but people kept coming back, even after graduation. . . . We spent hours on our own outside of class on this stuff.”

The students worked in their dorms translating military texts. They skipped movie nights for marathon sessions reviewing TV clips of missiles being moved from one tunnel structure to another. While their friends read Shakespeare, they gathered in the library to war-game worst-case scenarios of a Chinese nuclear strike on the United States.

Over time, the team grew from a handful of contributors to roughly two dozen. Most spent their time studying the subterranean activities of the Second Artillery Corps.

While the tunnels’ existence was something of an open secret among the handful of experts studying China’s nuclear arms, almost no papers or public reports on the structures existed.

So the students turned to publicly available Chinese sources — military journals, local news reports and online photos posted by Chinese citizens. It helped that China’s famously secretive military was beginning to release more information, driven by its leaders’ eagerness to show off China’s growing power to its citizens.

The Internet also generated a raft of leads: new military forums, blogs and once-obscure local TV reports now posted on the Chinese equivalents of YouTube. Strategic string searches even allowed the students to get behind some military Web sites and download documents such as syllabuses taught at China’s military academies.

Drudgery and discoveries

The main problem was the sheer amount of translation required.

Each semester, Karber managed to recruit only one or two Chinese-speaking students. So the team assembled a makeshift system to scan images of the books and documents they found. Using text-capture software, they converted those pictures into Chinese characters, which were fed into translation software to produce crude English versions. From those, they highlighted key passages for finer translation by the Chinese speakers.

The downside was the drudgery — hours feeding pages into the scanner. The upside was that after three years, the students had compiled a searchable database of more than 1.4 million words on the Second Artillery and its tunnels.

By combining everything they found in the journals, video clips, satellite imagery and photos, they were able to triangulate the location of several tunnel structures, with a rough idea of what types of missiles were stored in each.

Their work also yielded smaller revelations: how the missiles were kept mobile and transported from structure to structure, as well as tantalizing images and accounts of a “missile train” and disguised passenger rail cars to move China’s long-range missiles.

To facilitate the work, Karber set up research rooms for the students at his home in Great Falls. He bought Apple computers and large flat-screen monitors for their video work and obtained small research grants for those who wanted to work through the summer. When work ran late, many crashed in his basement’s spare room.

“I got fat working on this thing because I didn’t go to the gym anymore. It was that intense,” said Yarosh, who has continued on the project this year not for credit but purely as a hobby. “It’s not the typical college course. Dr. Karber just tells you the objective and gives you total freedom to figure out how to get there. That level of trust can be liberating.”

Some of the biggest breakthroughs came after members of Karber’s team used personal connections in China to obtain a 400-page manual produced by the Second Artillery and usually available only to China’s military personnel.

Another source of insight was a pair of semi-fictionalized TV series chronicling the lives of Second Artillery soldiers.

The plots were often overwrought with melodrama — one series centers on a brigade commander who struggles to whip his slipshod unit into shape while juggling relationship problems with his glamorous Olympic-swim-coach girlfriend. But they also included surprisingly accurate depictions of artillery units’ procedures that lined up perfectly with the military manual and other documents.

“Until someone showed us on screen how exactly these missile deployments were done from the tunnels, we only had disparate pieces. The TV shows gave us the big picture of how it all worked together,” Karber said.

A bigger Chinese arsenal?

In December 2009, just as the students began making progress, the Chinese military admitted for the first time that the Second Artillery had indeed been building a network of tunnels. According to a report by state-run CCTV, China had more than 3,000 miles of tunnels — roughly the distance between Boston and San Francisco — including deep underground bases that could withstand multiple nuclear attacks.

The news shocked Karber and his team. It confirmed the direction of their research, but it also highlighted how little attention the tunnels were garnering outside East Asia.

The lack of interest, particularly in the U.S. media, demonstrated China’s unique position in the world of nuclear arms.

For decades, the focus has been on the two powers with the largest nuclear stockpiles by far — the United States, with 5,000 warheads available for deployment, and Russia, which has 8,000.

But of the five nuclear weapons states recognized by the Non-Proliferation Treaty, China has been the most secretive. While the United States and Russia are bound by *****eral treaties that require on-site inspections, disclosure of forces and bans on certain missiles, China is not.

The assumption for years has been that the Chinese arsenal is relatively small — anywhere from 80 to 400 warheads.

China has encouraged that perception. As the only one of the five original nuclear states with a no-first-use policy, it insists that it keeps a small stockpile only for “minimum deterrence.”

Given China’s lack of transparency, Karber argues, all the experts have to work with are assumptions, which can often be dead wrong. As an example, Karber often recounts to his students his experience of going to Russia with former defense secretary Frank C. Carlucci to discuss U.S. help in securing the Russian nuclear arsenal.

The United States had offered Russia about 20,000 canisters designed to safeguard warheads — a number based on U.S. estimates at the time.

The generals told Karber they needed 40,000.

Skepticism among analysts

At the end of the tunnel study, Karber cautions that the same could happen with China. Based on the number of tunnels the Second Artillery is digging and its increasing deployment of missiles, he argues, China’s nuclear warheads could number as many as 3,000.

It is an assertion that has provoked heated responses from the arms-control community.

Gregory Kulacki, a China nuclear analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists, publicly condemned Karber’s report at a recent lecture in Washington. In an interview afterward, he called the 3,000 figure “ridiculous” and said the study’s methodology — especially its inclusion of posts from Chinese bloggers — was “incompetent and lazy.”

“The fact that they’re building tunnels could actually reinforce the exact opposite point,” he argued. “With more tunnels and a better chance of survivability, they may think they don’t need as many warheads to strike back.”

Reaction from others has been more moderate.

“Their research has value, but it also shows the danger of the Internet,” said Hans M. Kristensen of the Federation of American Scientists. Kristensen faulted some of the students’ interpretation of the satellite images.

“One thing his report accomplishes, I think, is it highlights the uncertainty about what China has,” said Mark Stokes, executive director of the Project 2049 Institute, a think tank. “There’s no question China’s been investing in tunnels, and to look at those efforts and pose this question is worthwhile.”

This year, the Defense Department’s annual report on China’s military highlighted for the first time the Second Artillery’s work on new tunnels, partly a result of Karber’s report, according to some Pentagon officials. And in the spring, shortly before a visit to China, some in the office of then-Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates were briefed on the study.

“I think it’s fair to say senior officials here have keyed upon the importance of this work,” said one Pentagon officer who was not authorized to speak on the record.

For Karber, provoking such debate means that he and his small army of undergrads have succeeded.

“I don’t have the slightest idea how many nuclear weapons China really has, but neither does anyone else in the arms-control community,” he said. “That’s the problem with China — no one really knows except them.”

Digging into China

Results 1 to 10 of 14

-

12-01-2011, 01:58 PM #1

Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

-

12-01-2011, 02:01 PM #2

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

Evidence of China’s nuclear storage system

-

12-01-2011, 04:27 PM #3

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

Dli bah naa man treaty sa U.S and Russia nga dli na mo increase ang china sa ila nuclear warhead...

-

12-01-2011, 06:16 PM #4

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

chuya ani oi. kron pa ko kita og ing ani dah. cool.

-

12-01-2011, 06:17 PM #5

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

mas daghan pa ni sa US oi sure ko, bisan pa man og ilang gi disassemble katong dako nila na bomb

-

12-01-2011, 07:36 PM #6Junior Member

- Join Date

- Dec 2011

- Gender

- Posts

- 39

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

all hail the redz!!!

-

12-01-2011, 08:37 PM #7

-

12-03-2011, 08:34 PM #8

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

wa nlang kwenta ang AREA 51 sa America

? ngita nsd ni cla ug rason aron mag gubot... ses... kusog kaau ni cla manghimantay pero ug cla questionon mag alibi daun..

? ngita nsd ni cla ug rason aron mag gubot... ses... kusog kaau ni cla manghimantay pero ug cla questionon mag alibi daun..

-

12-04-2011, 05:23 AM #9

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

mao gani naay UN ug peace treaties

-

12-04-2011, 06:42 AM #10

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

Re: Digging into China’s nuclear tunnels

Ang Russia sad I'm sure daghan na silag unaccounted arsenal and facilities related sa ilang nuclear ICBM programs sad. Since Soviet-era pa na ilang programs gud.

Advertisement

Similar Threads |

|

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote