The Decline of Fashion Photography

...An Argument in Pictures

by Karen Lehrman

Fashion photography is in fashion. This 1951 Vogue cover by Irving Penn recently sold for $28,750 at auction.

It is indeed brilliant: Penn's masterful use of light, balance, and a spare composition create an understated elegance.

Meanwhile, this image taken by one of today’s biggest celebrity photographers, David LaChapelle, recently went for $3,000.

Why does that seem like a worse deal than $28,750 for the Penn? Critics say the problem is that today's fashion photographers

see themselves as artists, while their Golden Age predecessors thought they were just working for a living.

[img width=500 height=320]http://www.slate.com/features/010510_fashion-slide-show/images/02_BurningHouse.jpg[/img]

True, fashion photography is commerce. But it is also art. One problem with today's fashion photography comes when

the photographer forgets to create art. For example, this spread from the February issue of Vogue shot by hotshot

photographer Michael Thompson. These images are as sterile and boring, as prosaic and plodding, as a Sears catalog.

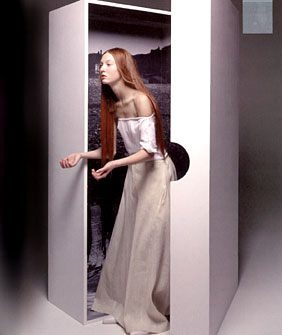

The other problem is the opposite. Sometimes the commerce is what gets forgotten. This image from the March issue

of Paper, a hip New York cultural magazine, may well be art, broadly defined. But does its self-conscious attempt to be

a great photograph undermine its effort to be a great fashion photograph?

The past 30 years aren't entirely barren of great fashion photographs. The work of two photographers in particular

—Sarah Moon (left) and Paolo Roversi (right)—has been both consistently original and beautiful. Moon’s images—muted,

shadowy, surreal—marked a significant break from the bland aesthetics of the '60s. And Roversi’s ethereal, painterly

images gracefully walk that line between elegance and edge.

Some of the better fashion photography today can be found in ads and catalogs rather than in magazine editorial spreads.

The latest Prada campaign, for example, is one of the more captivating fashion spreads of any sort in years.

What made Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue emblems of visual sophistication during the '40s and '50s was their visionary

art directors, Alexey Brodowich and Alexander Liberman, respectively. Both used only exceptional photographers

and then set their photographs off to maximum effect with a generous use of white space. Their goal was to turn

the fashion magazine into a luscious exotic escape.

Today, magazine layouts are jammed with gratuitous text, which often carelessly spills over onto the photo spreads.

The only art director to come close to the creative genius of the past is Fabien Baron, who did a major redesign

of Harper’s Bazaar in the mid-'90s under Elizabeth Tilberis.

When Tilberis died in 1999, Baron was ousted, and Harper’s Bazaar sank back to vying with Vogue for mediocrity.

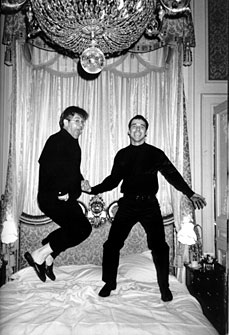

Fashion magazines today still use "name" photographers. But in getting a name, aesthetic appearance counts

as much as aesthetic judgment or imagination. That's because one duty of the modern fashion photographer

is to appear in magazine party spreads.

Editorial fashion spreads today tend to reflect either focus-group-induced blandness …

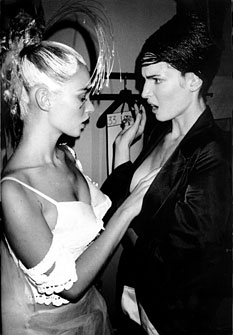

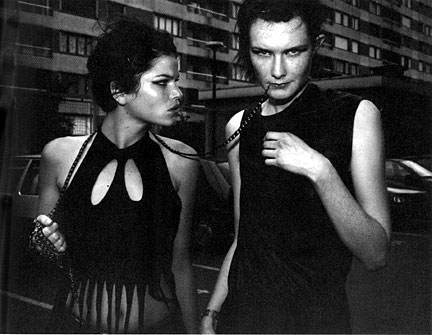

… or “notice me!” shock tactics left over from the Helmut Newton-inspired psycho-sexual-disability trend

of the late '70s and '80s.

After Newton came heroin chic. The grunge aesthetic taken to its logical extreme, this trend offered us

13-year-old sleep-deprived anorexics in desperate need of real clothing.

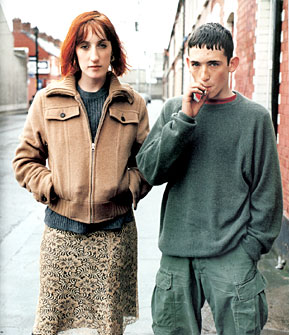

We’ve since moved up a notch, to what’s being called gritty realism. “Referencing” (that is, imitating) the

“urban and suburban narrative”-type photos of Nan Goldin and Cindy Sherman, followers of this trend claim

that by mirroring the real world, they are “challenging, exploring and questioning the truth in fashion.”

The products of these trends have three things in common. First, they’re ugly. Beauty has not been highly

valued in the art world in general for the past few decades, and even in much of the fashion world. The problem,

as Kennedy Fraser wrote in The Fashionable Mind, has been that beauty “seemed to represent a kind of authority.”

[img width=500 height=305]http://www.slate.com/features/010510_fashion-slide-show/images/15-FT-182.jpg[/img]

Fashion photography isn’t obligated to take readers into an elegant fantasyland, though that certainly was nice.

But it should be different from photojournalism, and especially photojournalism concentrating on society’s dark side.

Great fashion photography—like great art in general—doesn’t just “tell about today”; it speaks truths about yesterday

and tomorrow. As Nick Knight puts it, “If you want reality, why don’t you look out of the window?”

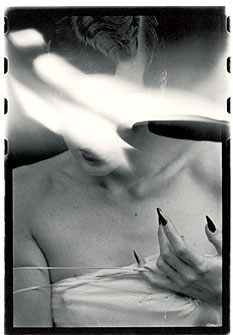

There’s a difference between expanding our notions of beauty—which the best fashion photography, like this image

by Peter Lindbergh, does—and purposefully making things ugly to score a political point.

Recent fashion photography also is more than a bit misogynistic. That is the second thing these various trends have

in common. If photographers and editors really cared about the role of women in society, they would use models

above the age of 20, who look like they could complete a sentence.

Photographers in the past tended to use models who seemed confident, intelligent, and sophisticated. Lisa Fonssagrives,

Penn’s wife, model, and muse, epitomized a woman of great strength and dignity. You didn’t just want to wear her clothes;

you wanted to be her.

Today, 30 years into feminism, we have models who look not just weak and unsophisticated, but also dumb

and victimized. Academic feminists haven’t complained because the models are supposedly playing a subversive role

and subversion is inherently politically correct. Moreover, many of the young photographers are female. But now

we’ve moved into “fashion vérité” and the models still look stupid. Is this how women in fashion see themselves?

The third problem with recent trends in fashion photography is the most basic: Very often the pictures don't show the clothes.

As with art in general, it may be easier to record or comment on society than to develop the skills necessary to

create a great photograph. While fashion photographers of the past—from Edward Steichen to Lillian Bassman below

—were steeped in art …

… many fashion photographers today aren’t even photographers first. Immediately prior to achieving his status

of celebrity photographer, Mario Testino was a waiter.

Testino’s photos offer the flip side of gritty realism—life with the beautiful, hip, and naughty—and are shot at

a slam-bam-thank-you-ma’am speed that leaves little time for creative cogitation. “I act by instinct,” Testino told

The New Yorker last September, “I do, and then I think.”

Meanwhile, some of most interesting and innovative work is being done not in fashion photography, but in fashion illustration.

[img width=500 height=334]http://www.slate.com/features/010510_fashion-slide-show/images/26_Giddio.jpg[/img]

Louise Dahl-Wolfe, one of Harper’s Bazaar’s pre-eminent photographers, created this image in 1950. She did not party

with fashion editors. The magazine did not publish pictures of her mingling with the models. Dahl-Wolfe in her professional prime

was quite plump and no beauty. But she created beautiful pictures that transcend time and place. To her editors and art director,

that’s all that mattered.

View Poll Results: Do you agree with this observation?... vote and tell us why...

- Voters

- 8. You may not vote on this poll

Results 1 to 2 of 2

-

07-07-2006, 06:44 PM #1

- Join Date

- May 2003

- Posts

- 2,672

The Decline of Fashion Photography...

The Decline of Fashion Photography...

-

08-28-2006, 09:48 PM #2Junior Member

- Join Date

- Aug 2006

- Posts

- 41

Re: The Decline of Fashion Photography...

Re: The Decline of Fashion Photography...

for some reason i miss inès de la fressange... nick knight still rocks i-D mag from time to time...

Similar Threads |

|

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote